Au hasard Balthazar

Some films do not narrate; they simply exist. Robert Bresson’s Au hasard Balthazar stands as one of the most radical expressions of this silence. The film follows the life of a donkey, yet it forces the viewer not toward an animal story, but toward the collapse of human morality. Bresson removes the human from the center, reduces language, trims the dramatic, and leaves behind a single question: How can innocence exist in this world?

The central thought of the film can be crystallized in a single sentence:

The human world is morally corrupted; innocence can exist in this world only through suffering.

This sentence is never spoken in the film. Yet it is continuously rewritten in Balthazar’s body, in his gaze, in his burdened steps. The donkey does not speak, does not object, does not calculate. Precisely for this reason, he becomes an ethical figure. Humans, on the other hand, speak, justify, fall silent, withdraw. Throughout the film, goodness exists—but it is ineffective. Evil exists—and it is resolute. And the majority, as always, sees and remains silent.

Balthazar, at the center of the film, is not a “character” in the classical sense. He does not speak, choose, or resist. That is precisely why he is universal. Balthazar is innocence in its purest form: without moral claims, without the capacity to defend itself. As he passes from one owner to another, each human reveals their own moral position. Thus, Bresson defines people not by their words, but by how they treat the powerless.

In this sense, the humans in the film are constructed not as individuals, but as moral types. Marie represents innocence within the human world: well-intentioned, fragile, defenseless. Yet innocence is not a protective armor in this world. Marie’s tragedy is not that she chooses evil, but that she lacks the strength to distinguish it from good. Her attraction to Gérard is not a moral deviation, but a psychological refuge. Power, decisiveness, and domination are mistaken for love. Here, Bresson makes a harsh yet realistic observation: innocence is drawn to power because it wants to survive.

The crowds, merchants, and villagers represent society itself. They see, they know, but they remain silent. Perhaps Bresson’s harshest judgment is hidden here: evil survives not only through tyrants, but through spectators. Indifference is not a moral void; it is active complicity.

At this point, Nietzsche’s critique of morality enters into a silent dialogue with Bresson’s camera. For Nietzsche, traditional morality is an illusion that attempts to make the world appear more just than it is. The world does not operate according to good intentions, but according to will, power, and determination. The world of Au hasard Balthazar is precisely this. Innocence is crushed not because it refuses to defend itself, but because it is too pure to do so. Suffering here is not purifying, nor is it ennobling. It simply exists.

“One is not surprised when birds of prey carry off small birds. But when the small birds say: ‘These birds of prey are evil, and we, who do not prey, are the good ones,’ then I begin to laugh. For nothing is more laughable than the innocence of those who believe themselves good because they lack claws.”

None of the characters in the film are “perfectly good.” Bresson does not believe such a figure belongs to this world. Jacques’ inactive goodness, the father’s principled yet powerless morality, the mother’s withdrawn compassion—all are well-intentioned, yet none are sufficient to protect innocence. This is precisely the morality Nietzsche criticizes: a goodness that produces no results, pays no price, and takes no risk.

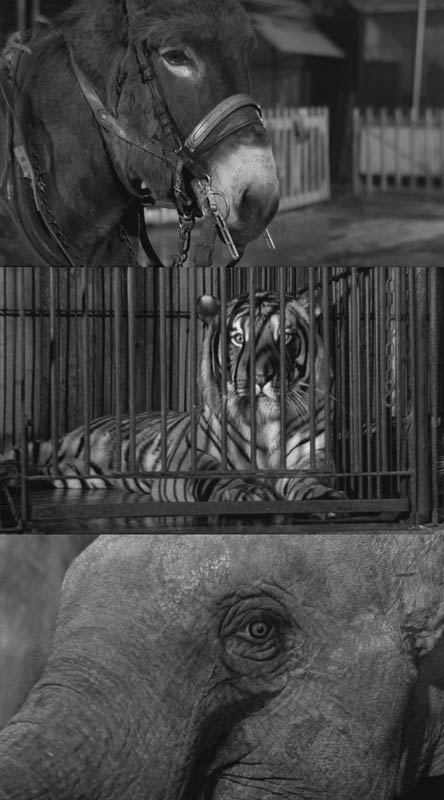

One of the most striking moments of the film occurs when Balthazar looks into the eyes of a circus elephant. Two animals, chained and silent, face one another. This encounter carries no meaning; it precedes meaning. There is no human, no language, no interpretation—only the nakedness of a shared fate. In this moment, human-centered morality is completely suspended. Nietzsche’s critique of humanity’s belief in itself as the center of the universe finds a cinematic counterpart here.

At this point, poetry falls silent—or withdraws.

İzzet Yaşar, You Will Never Write That Poem

you will never do in your poem

what bresson does in his film

the gaze exchanged between

a runaway pack donkey

and a circus elephant

you will never tell it

you will not even come close

to the unreachable fate of the four-legged

gazes woven from gazes

timeless salt nuns

if they could exist beyond your imagination

perhaps in moments of distraction

they might utter

such an impossible poem

such an inhuman poem

forgive me, all of you

wet noses

tails and wings

fins and shells

I wonder what you would say, turgut uyar

if there is poetry, there is poetry

but only this much

What the poem says—“you will never tell it”—is exactly what Bresson achieves. Because there is no narrative here, only existence. A realm language cannot reach. In Nietzsche’s sense, the courage to look at suffering without assigning it meaning. Bresson does not comfort the viewer. He offers no consolation. He distributes no justice. He simply shows.

Balthazar dies at the end of the film. But he does not become corrupted. Humans live on—but morally collapse. For this reason, the film is not a narrative of despair. Worse than that: it is a diagnosis. It does not show that the world is unjust, but how the idea of justice comforts us.

Au hasard Balthazar does not explain why innocence does not belong to this world. It leaves that truth quietly with us. And perhaps that is why, when the film ends, what remains is not a story, but an unsettling awareness.

This English translation was produced from the original Turkish text with the assistance of artificial intelligence, as it was considered to allow for a more precise and faithful expression. The translation has been revised.